The winding roads and blind corners of Highway 17 are known to Santa Cruz County residents as both dangerous and beautiful. The lush redwoods lining the heavy traffic route are teeming with local wildlife. Birds, deer, bobcats and foxes forage the rural mountain ranges alongside the corridor.

Yet none are as elusive and majestic as California’s golden mountain lions.

These giant cats cloak themselves in the trees, while below them, roughly 55,000 cars commute over Highway 17. With drivers speeding between the San Francisco Bay Area and the coast, the mountain lions (also known as pumas), have no safe way to cross the buzzing highway.

“There currently aren’t any under crossings or culverts more than about two feet in diameter,” says Nancy Siepel, a biologist and mitigation specialist for Caltrans.

This is a problem for big animals trying to find a route under the roadway.

Major highways like 17 dissect the mountain ranges pumas need to secure new territory, find food and avoid inbreeding. Severing long-ranging wildlife from their habitat introduces myriad problems, not just for the animal, but for the entire ecosystem. And, while some cats successfully make it across the highway, many others fall victim to speeding traffic.

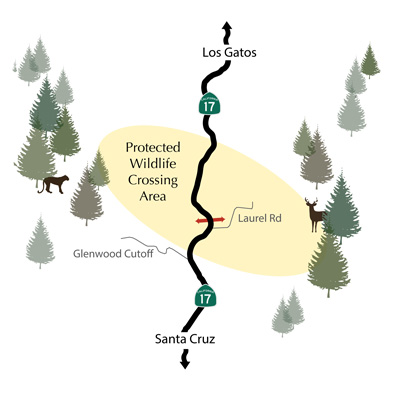

One such problem area is positioned two miles from the summit of Highway 17. A survey orchestrated by the Land Trust of Santa Cruz County revealed that the location, known as Laurel Curve, is the best possible place to build a wildlife passage. There are, by far, more animals trying to cross the corridor at this particular site than anywhere else along the highway.

“There is probably a deer hit, if not every week, every other week at Laurel Curve,” says Dan Medeiros, project manager at the land trust.

Laurel Curve is also known among locals to be high-risk for vehicular accidents. The heavy densities of wildlife crossing there adds pressure for both animals and motorists.

The Top Predator for Pumas: Humans

There are 4,000 to 6,000 pumas in California. While they are not an endangered species, they aren’t what you’d call thriving.

A 13-year study released last month in the journal PLOS ONE from the University of California, Davis, found southern California pumas have about a 56 percent chance of surviving through the end of each year.

“For an unhunted population, it’s shockingly low,” says Winston Vickers, who leads the Mountain Lion and Bobcat Project at U.C. Davis. “We managed to kill a lot of them ourselves.”

In fact, humans are responsible for the cats’ top two causes of death: accidental vehicle collisions and deliberate kills, either legal depredation or illegal poaching.

While it has been illegal to hunt large cats for sport in California since the passage of Proposition 117 in 1990, landowners can get a “depredation permit” if a cat is considered a threat.

The state Department of Fish and Wildlife helps homeowners learn how to avoid attracting mountain lions to their property. Yet depredation remains a main cause of death for pumas. From 1972 to 2013 state officials issued 6,175 depredation permits resulting in 2,816 puma deaths.

Over the last 19 years, three people have been killed by mountain lions, and state officials have verified 14 mountain lion attacks.

A Killer Curve

Pumas in the Santa Cruz Mountains face the same threats as the southern population, says Chris Wilmers, associate professor of environmental studies at U.C. Santa Cruz and head of the Santa Cruz Puma Project. His team has collared and tagged more than 60 pumas roaming the mountain forests.

There are only between 50 and 100 pumas altogether in the Santa Cruz Mountains; accessibility to neighboring ranges such as Hamilton or Gabilon is critical to their survival and to diversifying their species.

The land trust has dozens of wildlife cameras installed along Laurel Curve that show high densities of animals attempting to cross the highway. They have also gathered roadkill and collar data that confirms the animals’ activity.

According to state wildlife officials, 14 pumas have been killed on Highway 17 since 2007. Last year, of the 69 collisions reported at or around Laurel Curve, 9 of them were caused by animals. An adult male puma weighing about 150 pounds slamming into a car going at least the 50 miles per hour speed limit will probably kill the cat, and cause bodily harm to the driver.

Since 2011, the land trust has raised funds and purchased two of the three properties needed to build a wildlife crossing under the highway.

The last property sits to the west of Laurel Curve — 190 acres of untouched forest north of Scott’s Valley, called “Marywood.” It is owned by the Dominican Nuns of San Jose, and the land trust is currently planning a fundraising campaign for its purchase.

Wanted: Safe Puma Crossing

Many highways along California’s central coast have incorporated wildlife accommodations into existing culverts. But Caltrans’ Siepel says this would be the first project in Santa Cruz County built solely for the function of connecting wide-ranging animals to wildlands.

Both government agencies and non-profit organizations have supported the land trust’s efforts to purchase the pristine Marywood forest for a wildlife crossing. Medeiros expects the property will be expensive, but says it’s essential.

“The property has the ability to have four to five homes built there,” he says, “which would destroy the wildlife corridor.”

Two designs are being considered for the passageway. Both designs will have a 10-foot clearance and a 16-foot wide natural soil bottom. One design involves building a very large culvert under the highway. The second option would be to excavate a large passage under a section of Laurel Curve, basically turning it into a bridge.

The total project is estimated to cost around $10 million dollars. Caltrans and the land trust are currently exploring funding options, but don’t yet know where the money will come from.

First, the land trust must raise the funds to purchase Marywood by June 2016, and secure a conservation easement to protect it from development. The cost of Marywood is still in negotiation but is scheduled to be announced this fall.

If all goes according to plan, Caltrans estimates construction can start in 2021, and be completed about a year later.

This year, two pumas in the Santa Cruz Mountains had litters, giving birth to five kittens. The four male kittens will likely have the toughest time of it; in just a year-and-a-half they have to strike out on their own to find new territory. They won’t get much help crossing Highway 17. But if they can stay alive, their kittens’ kittens may someday discover a tunnel that provides safe passage under the killer curve.