Listen to the story:

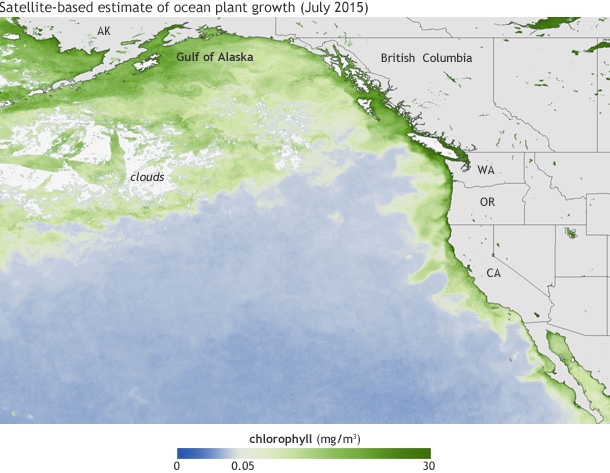

A toxic algae bloom that began off the West Coast this spring now stretches from California to Alaska. It’s poisoning marine life from shellfish to sardines to sea lions, and scientists say it’s one of the worst they’ve seen.

“We’ve never seen a bloom this big before,” says Anthony Odell, a research analyst with the University of Washington’s harmful algae bloom monitoring program. “It’s also one of the most toxic blooms we’ve seen.”

Odell is one of a rotating team of scientists who are studying the bloom aboard the Bell M. Shimada, a research vessel belonging to NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Equipped with state-of-the-art technology, the ship is traveling this summer up the west coast to British Columbia.

Odell says he’s seen a lot of toxic blooms, but this one’s different, partly because it consists of several species of harmful algae.

“It’s making a toxic plankton soup,” he says. “It’s pretty amazing to see all these things blooming together, because usually they prefer these different conditions so there’s definitely something unusual going on.”

Toxic algae blooms are not uncommon in the Pacific Ocean—they’re called red tides and they come in summer’s warm waters and dissipate in the fall. But the current algae bloom isn’t likely to dissipate.

The algae are thriving in unusually warm waters—in fact, abnormally warm water that scientists are calling “the Blob.” The algae bloom itself is an estimated 40 miles wide and, in some places, could reach a depth of more than two football fields, according to sonar readings. Scientists have been able to verify the presence of the algae bloom down to 45 feet by testing the water.

“From a scientific standpoint it’s fascinating,” Odell says. “From a sea life and human health view point, it’s pretty scary. Because it’s so big and it’s so toxic and it’s not really giving sea life a chance.”

One of the toxins the algae are producing is domoic acid. It’s a neurotoxin that doesn’t have negative effects on shellfish and fish. But it can kill other marine life because the micro algae—or phytoplankton—are the base of the food web.

“Everything in the ocean eats phytoplankton or eats something that eats phytoplankton,” Odell says. “So when you have one of these species that starts producing toxin, it works its way up through the food chain really fast. It gets into shellfish, it gets into crabs, it gets into small fin fish like sardines and anchovies, which are then fed on by salmon and pelicans and seals and sea lions.”

NOAA scientists say domoic acid from the algae bloom is responsible for the high number of seizures and deaths in California sea lions this summer.

Domoic acid can also poison humans, causing nausea and dizziness, or in worse cases, permanent short-term memory loss, and even death. That’s why fishery managers have shut down some crab fisheries in Oregon and Washington, and severely restricted fishery markets from California’s central coast.

“We’re now unable to market anchovy,” says Diane Pleschner-Steele, executive director of the California Wetfish Producers Association. “And there’s a small, kind of an ethnic market for anchovy for human consumption. And also, anchovy used for bait and for animal food. So we’re now prohibited from selling to the public.”

She said after the anchovy market collapsed, fishermen moved on to squid, which feed on a different plankton.

So far, there’s little sign the algae bloom is going to slow down and give sea life a break.

“There’s still quite a bit of toxin production going on,” Odell says, “and a rather sizable bloom.”

Although the unusually warm ocean water is one suspect, scientists still don’t know for sure the cause of the algae bloom. Odell says they’re researching whether climate change is contributing.

“There’s been an international consensus that climate change would affect harmful algal blooms in the fact that we would likely see more of them,” Odell says. “But there’s just not enough data to tie the two together yet.”

Scientists are scheduled to arrive in British Columbia in September. Then, it could take a few months to compile data before they can say more about what’s causing the toxic algae bloom, and what it means for the changing ecosystem of the Pacific Ocean.