Who says the grizzly bear has vanished from California? On the contrary, it’s nearly ubiquitous in the Golden State—on everything from the state flag to T-shirts and coffee mugs.

Of course, the bears themselves have been absent for nearly a century.

Before the Gold Rush, the best guess is there were probably 10,000 grizzlies in California. But in the space of about 75 years, they were trapped and hunted into extinction. Though no one can say with certainty when the last bear expired, by 1930 even unconfirmed sightings had winked out.

“They can be brought back,” insists Noah Greenwald, conservation director for the Arizona-based Center for Biological Diversity. In 2014, it petitioned the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to expand areas for grizzly recovery into California.

That petition was denied. The agency said it didn’t want to divert resources from its efforts to rebuild the brown bears’ populations elsewhere in the Lower 48. Currently wildlife officials estimate there are no more than 2,000 grizzlies spread across Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and Washington (with a much larger population in Alaska).

“Certainly in Yellowstone National Park, which gets more than three million visitors a year, grizzly bears are a tremendous draw there and a real source of joy,” observes Greenwald.

And yes, they can be a source of danger. A female grizzly with cubs killed a hiker in Yellowstone last year—but bear attacks are exceedingly rare. So the Center for Biological Diversity is betting on taking its case directly to the public. It’s gathered about 13,000 signatures on an online petition, and is about to launch the next phase of a web and social media campaign under the banner, “Bring Back the Bear.”

“I do think it’s something—with some education and with further study—something that people could and will rally around,” Greenwald speculates.

Hollywood hasn’t exactly advanced the cause, doing for Grizzlies more or less what “Jaws” did for sharks—last year’s Oscar nominee for best picture being only the latest example. Leonardo DiCaprio’s violent encounter with a mama grizzly was likely the most talked-about scene in “The Revenant.”

There Are Bears—And Then There Are Grizzlies

Right now, the only encounter possible with a native California grizzly, is at the California Museum in Sacramento, where Monarch, the bear that served as a model for the state flag, stands stuffed behind glass walls.

Clearly some prefer their grizzlies that way and they’re not alone. State wildlife officials are, to say the least, skeptical of the bid to reestablish the bears in California.

Listen to the Story:

Yellowstone grizzly recording by Bernie Krause/Wild Sanctuary

Marc Kenyon is a bear biologist; a big, bearded bear of a guy himself, Kenyon heads the state’s Human-Wildlife Conflict Program.

“That grizzly would turn this thing into a tin can in a hurry,” says Kenyon, showing me the trailers his agency uses to trap and transport injured or wayward black bears.

Kenyon’s agency puts the number of black bears in California at somewhere between 30,000 and 60,000—but clearly black bears are not grizzlies, which can easily be twice the size, a thousand pounds or more. And even though the bears would be placed in remote areas, there’s no guarantee they would stay put.

“One thing I can tell you about bears is that bears roam,” says Kenyon. “And they’ll roam a long distance.”

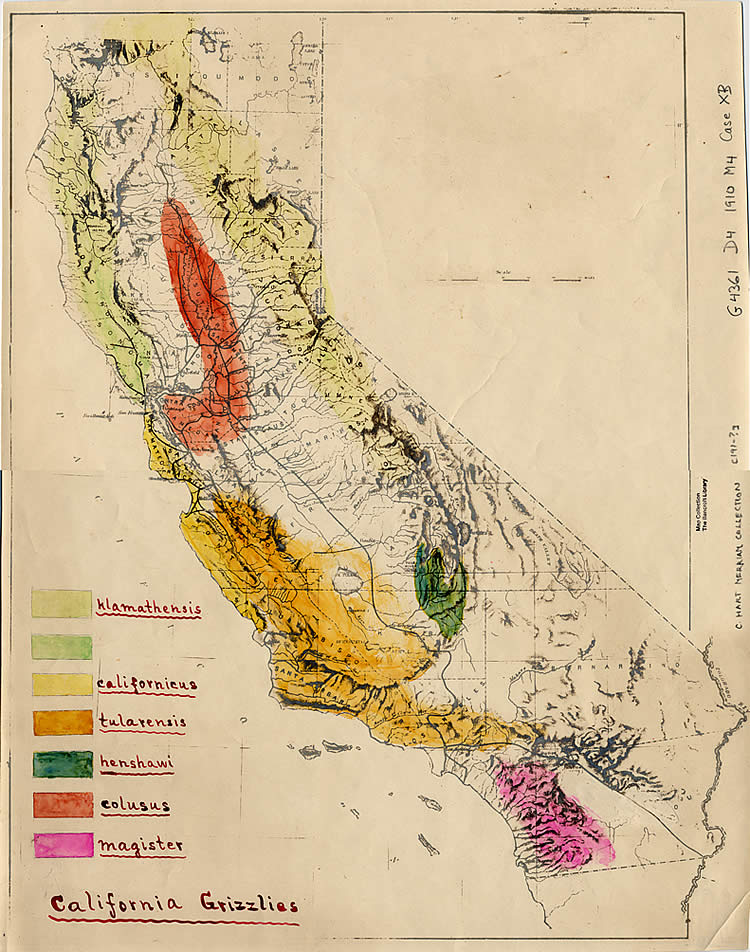

The Center for Biological Diversity has identified nearly 8,000 square miles of potential habitat in the remote Sierra Nevada, with a smaller area near the Oregon border. Kenyon’s not sure it’s enough.

“I can only imagine how far a grizzly bear in California might roam,” he says, “in search for food, in search for mates, in search for its own habitat, its own territory.”

Even advocates, like nature journalist Jason Mark, concede that this wouldn’t be an easy lift.

“I don’t want to at all underestimate the challenge of something ambitious like this,” says Mark, author of “Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man.”

He says the hardest part might be “changing the way that we think of what wild nature is good for.”

“Is it good, for us, just as a place to go recreate and watch and look at, or does wild nature have some intrinsic rights of its own?” he asks. “And in that sense the bear does have a right to return to what was once its homeland.”

Mark says the large carnivores could have ecological benefits, aiding in seed dispersal and balancing populations of smaller prey animals.

But Kenyon isn’t convinced that it’s the best thing for species like California’s declining deer population, or even for the bears themselves at this point.

“For a stable grizzly bear population, we’re looking in excess of 200 animals—that can find each other,” says Kenyon. By comparison, the Yellowstone grizzly population numbers about 700.

“If you get down to a density where the animals can’t find each other, you’re lessening the chance for them to breed,” he says, “and then you’re lessening the chance for the species to survive in the long term.”

Grizzlies … in Oakland?

Which brings us to the Oakland Zoo, where construction crews have started work on its California Trail project. The exhibit will feature the state’s iconic critters from big cats to condors, and the centerpiece will be a three-acre grizzly “habitat.”

“You know, unfortunately they tell sort of the sad history of humans and wildlife here in California,” says Colleen Kinzley, who directs animal care, conservation and research at the zoo.

“We want people to be aware of that,” she says. “I mean, despite the fact that the grizzly bear is on our flag and our state seal, many people don’t know that grizzlies existed in California and are really a part of this habitat and environment.”

The zoo is preparing for its first bears-in-residence sometime next year. And Kinzley says the best way to “bring back the bears” in the wild would be to let them come back on their own.

“You can’t just plop a large predator into a location and say, ‘Alright, everybody just get along,'” she says. “The bear will lose if you don’t have complete buy-in from all the different constituencies.”

It would be a long shot, to be sure, but it’s theoretically possible that, say, the tiny population of grizzlies in the Washington Cascades might work their way down into California, much as wolves have drifted down from Oregon.

“It would be a long way off but I think probably easier than getting everyone to agree to bring bears from somewhere and put them in California,” says Kinzley. Kenyon agrees.

In any case, it’s likely that for a long time to come, the only way to see live grizzlies in California will be with a big fence around them.

Featured art by Laura Cunningham, author of A State of Change and co-founder of the desert conservation group Basin and Range Watch.

Source: Center for Biological Diversity (Teodros Hailye/KQED)

Source: Center for Biological Diversity (Teodros Hailye/KQED)