In the mid-19th century, there were as many as 10,000 brown bears in California — a greater population density than in Alaska today. The last documented sighting was in 1924. Now all that remains is the profile of the powerful bruin on the state flag.

No doubt some people will freak out at the prospect of the Lower 48’s biggest predator haunting the woods. But there are good reasons to return the animal to the Bear Flag Republic. Grizzly reintroduction would have clear ecological benefits. And it would have cultural benefits, too, by prompting us to rethink what nature is “good for.”

California is already crawling with predators. We have mountain lions in Los Angeles — where the Internet-famous “Hollywood Lion” stalks mule dear in Griffith Park — and one in San Francisco, too, where a cougar was captured on a security camera last summer.

The reappearance of mountain lions is an example of what conservation biologists call “rewilding.” In some instances, like that of the mountain lion, the wild animals find their way back on their own. In other cases, state or federal agencies have made determined efforts to bring back animals hunted and trapped to oblivion or pushed out by development.

The reintroduction of gray wolves to the Northern Rockies in the late 1990s is the best-known rewilding story. Twenty-one years after wolves were returned to Yellowstone National Park, there is an established population and some have migrated as far as Northern California, where, in August, a pack was confirmed in the state for the first time since 1924.

The return of the gray wolf to the rural West has been hugely controversial, marked by serial court cases, Capitol Hill maneuverings, vigilantism (in the form of poaching animals listed as endangered) and fiery debates that have scorched western communities. For many ranchers and hunters, the return of the wolf represents a dangerous surrendering of human control over the landscape. To supporters of rewilding, the success of the wolf is a kind of ecological restorative justice.

Bringing back grizzly bears to California is the latest rewilding idea. Last year, the Center for Biological Diversity, an Arizona-based conservation group, filed a petition with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to consider reintroducing the grizzly in the Southwest and California. The agency denied the request, and now the organization plans to petition the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to bring back the bear.

“Grizzly bears were a common part of the California landscape and had been there for eons, and we wiped them out,” says Noah Greenwald, the endangered species coordinator at the Center for Biological Diversity. “By bringing them back we would be righting a historic wrong.”

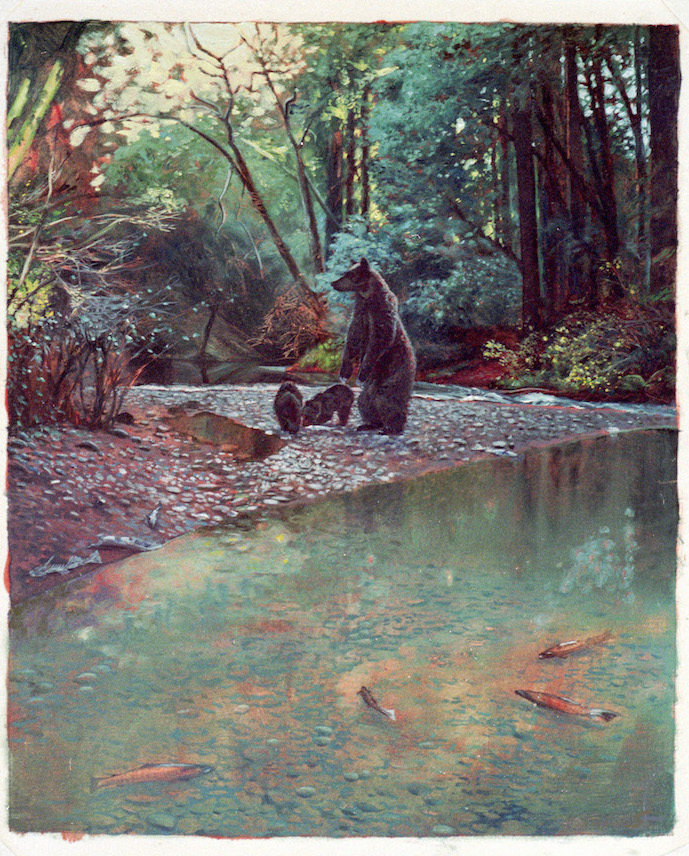

Returning grizzlies to California would have real ecological advantages. Wildlife biologists have shown that restoring large predators to a landscape can have consequences that ripple across an ecosystem. This phenomenon is called “trophic cascades.” Imagine: a wolf reappears on the scene. Suddenly, the elk and deer have to be alert. Their newly cautious behavior gives aspen and willow a chance to thrive, which provide fresh habitat for beaver and songbirds. David Mattson, a lecturer at the Yale School of Forestry, says grizzlies would have “demonstrable ecosystem effects” were they reintroduced to California. Brown bears would assist with seed dispersal and soil aeration as they tear into the ground hunting for gophers and voles. Coastal grizzly would move nutrients upstream and inland via their consumption of spawning salmon.

But state wildlife officials are cool on the idea. “Grizzly bears traditionally would roam oak woodlands and even beaches and eat whale carcasses and whatnot,” says California Fish and Wildlife spokesperson Jordan Traverso. “So you’d be introducing them in places where people are now, not the typical black bear habitat. So we are not supportive of that proposal, even a little bit.”

Still, the idea is not as outlandish as it might sound.

A study of Europe published in the journal Science found that large carnivores are successfully sharing landscapes with people. Some 17,000 brown bears (Ursus arctos, essentially the same species as the North American grizzly) live in 22 European countries, making the bear the most abundant large carnivore on the continent. Europe is also home to 12,000 wolves, twice as many as in the United States, despite the continent having twice the population density. The study found that large carnivores “have shown an ability to recolonize areas with moderate human densities if they are allowed, and to persist in highly human-dominated landscapes and in the proximity of urban areas.”

Martin Lewis, a geographer at Stanford who has studied the politics of rewilding, says the problem with grizzly reintroduction is not a lack of suitable habitat. But, he says, “there are questions about coexistence. People can learn to live with them, but there will be trade-offs. There will be encounters, and some of those encounters will be negative.”

Let’s face it. Wolves eat cattle and prized game like elk. Grizzlies sometimes attack backpackers. Mountain lions sometimes go after hikers. Acknowledging such dangers is not being callous toward human life, but recognizes that the lives of these animals, and the role they play in the environment, also matter.

The risks are worth it. The presence of grizzlies and mountain lions and wolves are reminders that nature in its wilder states is not here to serve us, and that wild animals and wild places have their own interests. Can we cohabitate with wild animals though they might pose a threat to us?

Such coexistence will require us to rethink some of our assumptions about wild nature. Do we want nature to always conform neatly to human desires — a garden to be tended by our hands, or an idyllic retreat imagined by the Romantics? Or are we willing to live with a nature that is wilder? A nature that is uncontrolled, unpredictable, and possibly dangerous. One where you could end up as lunch if you’re not careful.

To accept the return of large carnivores will demand a selflessness to which, as a species, we are unaccustomed. It will also require a measure of courage. After all, it’s easy to love a nature that just looks pretty. It’s a much more difficult task to live with a nature that can be threatening — a wolf pack in the pasture, a lion on the prowl under streetlights and, yes, grizzlies in the woods.

Jason Mark is the author of “Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man” and editor of Sierra magazine.

Featured art by Laura Cunningham, author of A State of Change and co-founder of the desert conservation group Basin and Range Watch.