You’ve seen a burst of headlines in Bay Area news since January about Zika virus in California. This year, state health officials have confirmed 11 cases, three of them recently in the Bay Area. The good news is, all of those people contracted the bug while traveling abroad. The question now is whether that could change.

Not likely, say most public health officials.

“I think the headline could be: Here in California, we are privileged that we don’t have the conditions for transmission of Zika,” says UCSF epidemiologist Jaime Sepulveda, who spoke recently at a Zika symposium hosted by the university.

Before we elaborate on why he says you don’t need to worry about the disease, let’s review a few basics.

What’s Zika?

Zika was discovered in 1947, and until now human outbreaks were contained and infrequent. It’s found in the same family as yellow fever, chikungunya, and dengue and is now spreading rapidly in Central and South America and the Caribbean.

Until last fall, Zika was thought to be a mild tropical disease that caused flu-like symptoms like a rash or red eyes, maybe a fever. It’s generally so mild people often don’t know they have it; 80 percent of Zika patients don’t have any symptoms.

How Does It Spread?

The disease is spread primarily by Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, when one bites an infected human and then bites another human.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says there are three secondary ways people can get Zika: it can be transmitted by a blood transfusion, a man can pass it along during sex, or a woman can pass it to her fetus. You can’t get Zika through smooching or casual touch such as shaking hands.

Why Are We Having an Outbreak Now?

Last fall, an unusual number of babies in Brazil and other countries were born with a neurological condition called microcephaly, a rare disease causing an infant’s head to be abnormally small.

The link between microcephaly and Zika is not scientifically proven yet, but the evidence is mounting. The rate of babies born with the condition is 30 times higher right now in Brazil than previous years.

On February 1, the World Health Organization declared Zika virus a public health emergency.

“Zika virus presents a pregnant woman’s worst possible nightmare,” says Kirsten Salmeen, a perinatologist at UCSF medical center. “She might not know if she was infected. She might not be able to avoid infection. And, if there is an impact on her fetus it might not be diagnosed until the late third trimester.”

Public health officials are warning pregnant women to avoid traveling to more than three dozen countries, and if they do visit, the recommended protocol is to lather on bug spray and wear long sleeves. There’s no vaccine for Zika virus.

Scientists also recently discovered Zika in the blood of 42 people suffering from Guillain-Barré syndrome — an autoimmune disorder that causes nerve damage and often severe, if impermanent, paralysis.

Zika Mosquitoes Are Different

The non-native insects look different from California mosquitoes, and don’t behave the same way. The Zika carriers bite people during the day, and they don’t travel; they’ll stay within about a quarter mile of where they’re born. They might spend their whole life behind your bedroom curtain, or in your closet, if they were able to get there in the first place.

“They really need to be spread by human activity,” says Megan Caldwell, spokesperson for the San Mateo County Mosquito Vector Control District.

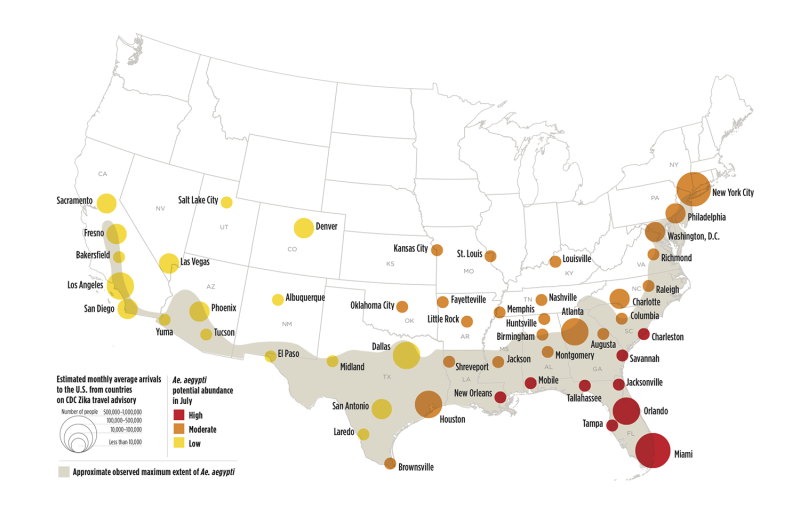

Experts think the Zika mosquitoes hitched a ride to California on a shipping container from Asia in 2011. They thrive in tropical weather, and have spread mostly in southern California. But, there are a few isolated pockets in the Bay Area.

“To date it’s only been found in San Mateo county in a small area of Menlo Park and Atherton,” Caldwell says.

But she emphasizes that eradication efforts are working. The county hasn’t found an Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus since May of 2015. Vector Control District officials will consider the mosquito eradicated in the county if they go a full two years without spotting one.

How to Keep the Pests Away

Vector ecologists advise homeowners to remove all standing water from their yards. Every drop of it. The Zika mosquito can develop in as little as a millimeter of water.

In other words, scrub and dry buckets every week, tighten screens on rain barrels, and check for leaky faucets. Don’t let water stand in plant saucers.

What Officials Are Doing

Eradication programs include house-to-house inspections, mosquito population surveillance, and elimination of standing water where mosquitoes may breed. Officials are setting traps anywhere Zika mosquitoes have been found. The traps can be as simple as a wooden tongue depressor wrapped in a coffee filter and then placed in a cup filled with water.

Will Zika Spread Here?

California winters ordinarily get cold enough to kill off the non-native insects, but the last few years have been unusually warm. Health officials warn hotter weather could bring more mosquito-borne diseases to California. But scientists add that many factors influence whether and when diseases like Zika could break out here.

“I think globalization and the movement of people and the movement of cargo is probably more of the story,” says Chris Barker, an entomologist at UC Davis. “So any effects of climate change are going to be very difficult to tease out.”

Barker says even if this summer is unusually hot he doesn’t predict a large mosquito-triggered outbreak in California because most people have either window screens or air conditioning. Plus, he says the state’s pest control is one of the best in the country.