Last week a group of 48 scientists, in the prestigious journal Science, urged America to launch a national project to study microbes. The next day, eminent scientists commenting in Nature, a journal of like prestige, said we should launch a worldwide effort to study microbes.

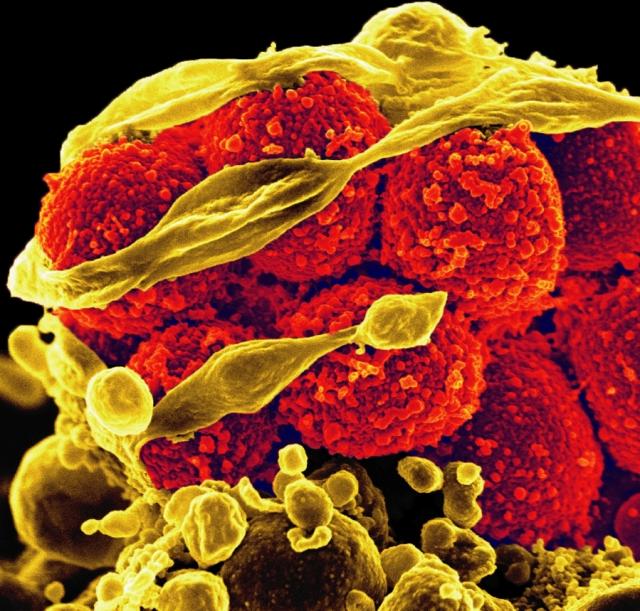

This is not a farfetched idea. If you put all life on Earth upon a scale, the weight of microbes would exceed all the rest put together. Microbes are within us and around us. We cannot survive without them.

In “The Hidden Half of Nature,” geologist David Montgomery and biologist Anne Biklé underscore the importance of microbes. “Consider the many microbial landscapes composing our bodies, from the river valley of our gut, to forests of hair, dry toenail deserts, and the skies of our eyes. These places have a multitude of interacting inhabitants and are as dynamic as any other ecosystem on Earth.”

Microbes: From Curiosities to Powerhouses

The invisible world of microbes was unknown until the 1600s, when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek devised a powerful microscope. Whatever he put under its lens — rainwater, the plaque from his teeth, cheese — he found it teeming with “animalcules,” tiny living things.

In the 1800s, Louis Pasteur showed that microbes called yeasts are essential for fermenting wine and beer. He proved that microbes are responsible for souring milk and decomposing meat. Sterilization and isolation of pure microbial cultures were great advances in feeding the world.

Later we learned that other microbes have the power to cause disease. This time, sterile practices and isolation revolutionized medicine.

Given this history, many people think of microbes only as germs to be eradicated. But recent research shows that communities of diverse microbes form invisible ecosystems, called microbiomes, supporting the ecosystems of the visible world — forests, lakes, agricultural fields and us.

In my own field of geology, we’ve learned that microbes are crucial agents in weathering rocks, depositing ores and preserving fossils. We’ve learned that microbes, the oldest form of life, were responsible for putting oxygen in the atmosphere over 2 billion years ago. “We will never escape our microbial cradle,” Montgomery and Biklé write.

Everywhere we look, we find a dizzying expanse of microbial mystery. Our very life — soil productivity, human health, global climate and more — is intimately tied to this universe of microbiomes.

Studying Our ‘Microbial Cradle’

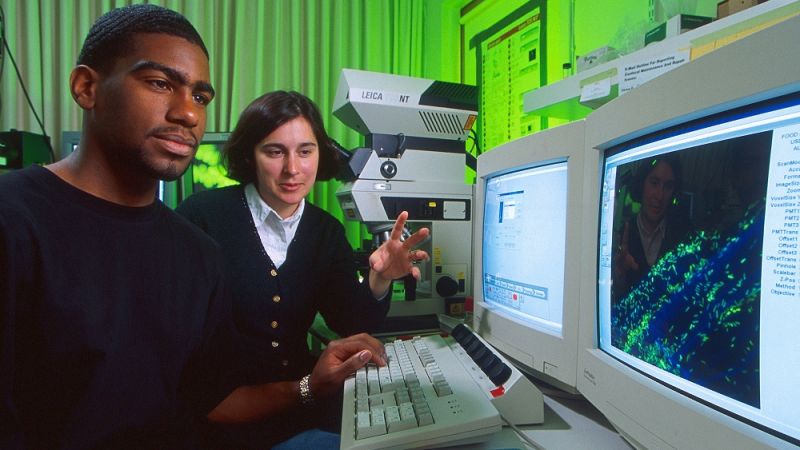

We know as much about microbes today as we knew about the sky before telescopes. Our current tools for sequencing DNA, familiar for solving crimes and studying our ancestries, are the equivalent of Leeuwenhoek’s first microscope.

When we turn those tools upon ordinary soil, we find it swarming with genetic material, but we recognize less than 1 percent of it. The same is true of the microbiome inside the human gut. The same is true of seawater.

The authors of the Science paper, therefore, propose “an interdisciplinary Unified Microbiome Initiative to discover and advance tools to understand and harness the capabilities of Earth’s microbial ecosystems.”

For example, better technologies could tell us what specific genes do, sequence the DNA of individual microbes, decode the “chemical conversations” in microbial communities and experiment on lab-based microbiomes.

Improve Health, Replenish Soil

It’s likely the first targets of this microbiome research will center on human health. Montgomery and Biklé say the proposed initiative will help us better understand “the unintended scrambling of the human microbiome through drugs like antibiotics, low-fiber diets, and other factors.”

Replenishing the world’s soil is another worthy target that can help us draw down the greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. The carbon sequestered in soils outweighs all the living mass in plants and animals. Thus increasing the organic matter in soil will rely on learning to work well with microbes.

Success in those fields will help us meet the greater challenge of the oceans. It’s a virtually infinite space filled with species we’ve barely begun to count, plus free-floating genes that can move between microbial species. It has evolved for billions of years. You could call the ocean Earth’s gut. As geology, biology and climatology converge in the study of the past and present ocean, microbiome studies will have a scientific payoff for centuries to come.

“We and the planet will be a lot better off the sooner we embrace and work with, rather than against, microbiomes,” Montgomery and Biklé say. “It may be our best way yet of gaining headway on some of humanity’s long-standing conflicts with the natural world of which we are a part.”